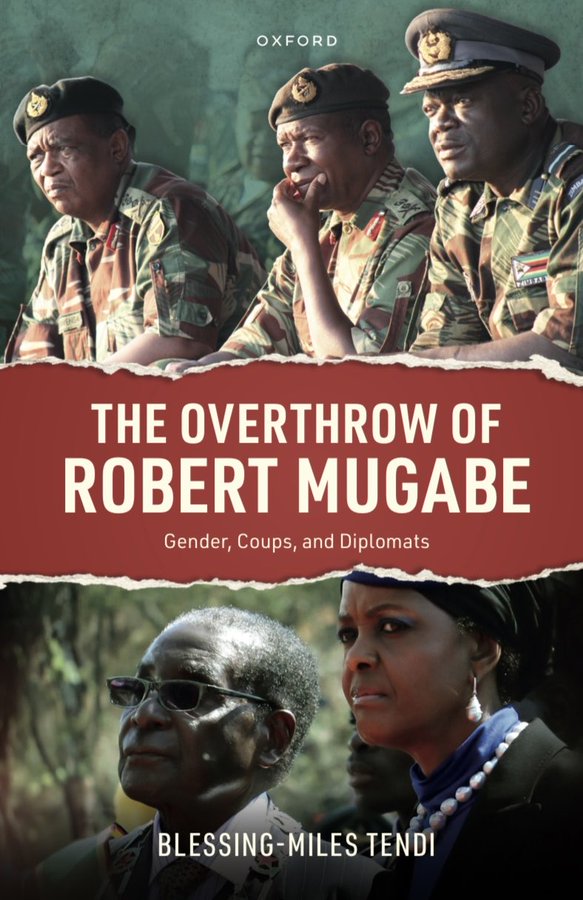

Illustrative image Daily Maverick| PART 2: The following is another Maverick Citizen report follow up to their first item which names President Emmerson Mnangagwa as one of the cartel bosses whose patronage and protection keeps cartels operating in Zimbabwe.

Here are the extracts from the part 2:

The report finds that there is consensus across political parties, academics, and wider society that cartels “go against the public interest” and are characterised by collusion between the private sector and influential politicians to attain monopolistic positions, fix prices and stifle competition.

In Zimbabwe, as the report finds, “institutions for regulating property rights, law and finance have been ensnared, and are actively abused to facilitate rent-seeking by cartels”.

It finds two key motivations for cartels – rent-seeking and political financing – and finds a close symbiotic relationship between actors that seek self-enrichment through rent-seeking and the ZANU-PF party, which seeks funding that can be illicitly channelled from government to the private sector.

The cartels impact Zimbabweans in multiple ways – entrenching their patrons’ hold on power, retarding democratisation, destroying service delivery for citizens and creating an uncompetitive business climate. All this leaves Zimbabweans poorer and increasingly under-served by their government and disempowered to hold the state to account.

The word “cartel” is used widely across Zimbabwean society to describe corrupt business practices with the collusion of political leaders.

One journalist interviewed for the report put it more bluntly: “Cartels and the ruling elite are one and the same thing”.

Rent seeking

Cartels are formed to transfer wealth from consumers and public funds to participants in the cartels (this is what we call “rent seeking”). The undeserved or unearned profit that rent-seekers gain is defined by economists as an “economic rent”.

Economic rents in Zimbabwe fall into two categories – natural rents and man-made rents.

Man-made rents arise from:

- Policy decisions that give rise to, for example, monopoly positions for some market actors, provision of publicly funded subsidies (which artificially reduce costs of production for some market actors), and cheap foreign currency;

- Illicit activities by private market players which include tax evasion and trade misinvoicing; and

- Illicit activities such as bribery and corruption.

A man-made economic rent, therefore, is the unnecessary portion of a payment that is made for goods or services, simply because the producer has the market power to charge it. This rent is also a social welfare loss, as Zimbabwean society could have gained the same goods and/or services without paying as much.

Economic structures that enable cartels include a notoriously unstable macro-economic framework, dependence on finite resources such as land and minerals, and the size of Zimbabwe’s predominantly informal economy.

The role of the private business sector

These structures create a perfect storm in which the private sector is incentivised to target public expenditure (public tenders) as its main source of income by colluding with public officials. This outcompetes Zimbabwe’s huge informal sector’s prices by avoiding taxes and statutory fees.

The private sector also actively seeks ways to avoid the impact of macroeconomic instability on its revenues and savings by, for example, externalising foreign currency or colluding with public officials to guarantee access to scarce foreign currency from the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ). These economic structures create unfair conditions and further enable cartel activity.

Social structures also serve to enable cartel behaviour through the co-option of traditional leaders and the largely neutral stance of churches on politics, which has weakened society’s response to the excesses of the power of the state.

Cartel types

The report finds three types of cartels in existence in Zimbabwe:

- Collusive relationships between private sector companies;

- Abuse of office by public officeholders for self-enrichment; and

- Collusive relationships between public officials and the private sector.

One example of the collusive relationships between private sector companies relates to the under-reporting of tobacco invoicing. In 2019, China and South Africa reported to the UN’s Comtrade system 55 and 85 million kilograms of tobacco imports from Zimbabwe, respectively, at an average price of US$9.06 per kg.

Zimbabwe, however, in the same year, only reported exports of 4.8 million kilograms of tobacco to China at an average price of US$7.46 per kg and 141 million kilograms to South Africa at an average price of US$5.34 per kg.

This points to under-pricing of exports, where tobacco, which is being directly exported to China at market price, is purported to be exported to a South African middleman who receives the payment from China, retains a significant amount in South Africa, and remits a smaller amount to Zimbabwe as the export price.

Given that 99.5% of tobacco exported to China from Zimbabwe between 2014-18 was falsely declared as exports to South Africa, there are clear indications that certain exporters are colluding to keep export prices low.

The Gold cartel

An example of both abuse of office by public officeholders for self-enrichment and collusive relationships between public officials and the private sector relates to Zimbabwe’s Sabi gold mine and, more broadly, to the changes of ownership in the formal gold mining sector since the 2018 coup.

Shortly after independence, the government acquired Sabi through a State-owned enterprise (SOE), the Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation (ZMDC). At the time, gold prices were high (US$850 per ounce after adjusting for inflation). By 2002 however, a deterioration in the macroeconomic environment in the country and a drop in gold prices (down to US$450 per ounce) led to the closure of the mine between 2002 and 2003.

Despite rising gold prices in the years thereafter, attempts to find investors to help resuscitate the mine were futile as the macroeconomic and political environment continued to deteriorate.

The mine reopened in 2016 and output reached 240kg per annum by 2018. A quadrupling of the gold price over the last 25 years has vastly increased the economic rents generated from mining gold and attracted greater attention from rent-seekers.

In mid-2020, as gold prices reached 25-year highs, the ZMDC shareholding in Sabi was reportedly in the process of transfer to Landela Mining Venture, a subsidiary of Sotic International – both of which, according to the report, are owned by Kudakwashe Tagwirei, a businessman who is an advisor to President Emmerson Mnangagwa and widely regarded as a key benefactor of ZANU-PF. Mnangagwa himself has said that Tagwirei is a relative – “my nephew”.

Landela was also said to have signed agreements to buy ZMDC’s equity in three other gold mines. In 2018, the Zimbabwean press reported that Tagwirei had gifted luxury vehicles to President Mnangagwa, Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga, Minister for Agriculture Perrance Shiri, and other ZANU-PF senior officials.

According to reports of court proceedings, Chiwenga later admitted to receiving a Mercedes Benz and a Lexus via the government’s Command Agriculture Programme, an initiative allegedly bankrolled by Tagwirei.

Daily Maverick