By Alex Magaisa

The resurgence of political violence

A review of political events over the past fortnight might suggest that the ZANU PF regime is back to form when it comes to political violence. After all, it’s a party whose fluency in the language of political violence is well known.

But that narrative is likely to miss the more subtle details of what is happening. A more nuanced analysis might reveal a lot more that is lurking in the background.

While popular narratives trace the recent spurts of violence to ZANU PF, this broad brush might likely miss the authors of the violence and their motives.

It is important to examine the authors of this violence with the state and ZANU PF. It’s a question that this BSR attempts to examine.

Before we examine this question, let’s consider the context in which the recent violence has occurred. The ugly incidents of violence marked a return of more visible opposition political activity after more than a year of a pandemic-induced lull.

Like its peers across the world, the Zimbabwean regime responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by imposing restrictions across economic, social, and political life.

This meant most political activities were prohibited. It was a difficult time for politicians, especially in the opposition parties.

While ruling parties could be seen in action responding to the pandemic, opposition parties tended to retreat to the background. The best they could do was to monitor the government’s response to the pandemic and identify weaknesses.

But they had to be careful lest their criticism was seen as petty or standing in the way of what most saw as an existential threat to humankind. But even as they were immobilized by the lockdown, opposition leaders faced mounting criticism.

“They have no plan” “They have no strategy”. These were some of the shots that were fired at Chamisa and the MDC Alliance.

While some countries took a more flexible approach, holding elections during the pandemic Zimbabwe took a more restrictive approach.

While neighbours Zambia and Malawi held national elections during the pandemic period, Zimbabwe suspended all electoral activities. However, political parties were still allowed to remove MPs from Parliament during the pandemic.

This mismatch created a massive gap that has left several constituencies without political representation. And although the regime has since opened other sectors of social and economic life, political restrictions are still in place.

This is not entirely surprising: there was always a fear that regimes of an authoritarian type would take advantage of the pandemic to reinforce their grip on power.

Court of Public Opinion

Against this background, it is hardly surprising that Chamisa’s recent foray into some rural areas has created quite a wave of excitement in the political community.

After a miserable year in which the MDC Alliance was subjected to a sustained political assault by ZANU PF and its surrogates, Chamisa relished the opportunity to reconnect with the ordinary citizens and demonstrate that he still has sufficient political capital.

The party had lost its headquarters, its MPs and councillors were removed by the Douglas Mwonzora outfit, its funding from the state was usurped and things were looking dire. Attempts to fight the battles in the courts of law were futile.

That is why at the time, the BSR said if there was going to be any respite for Chamisa, it would not be in the courts of law but the court of public opinion. But with the pandemic raging and restrictions in force, the court of public opinion remained closed.

The unavailability of the court of public opinion meant that official judgment on the authentic opposition remained in abeyance. The situation favoured the Mwonzora outfit because while they were allowed to remove MDC Alliance MPs, they did not have to worry about proving themselves in by-elections.

Unsurprisingly, they do not fancy by-elections or any elections at all. While they justify this aversion to elections on the seemingly noble ground that there ought to be reforms first, the reality is that they have no interest in electoral contests because they lack the political capital to win anything of significance.

They owe their status to the political capital accumulated by and stolen from Chamisa and the MDC Alliance in the 2018 elections. They know their relevance hangs on the façade created by the courts and the regime during the pandemic.

An election will cause their instant evisceration from the political scene, after which they will cease to have any claim to relevance. ZANU PF knows this too, and because it wants to frustrate Chamisa and the MDC Alliance, it has maintained the ban on by-elections.

The current tour is Chamisa’s first opportunity to test the political waters after more than a year of pandemic-induced absence. Two important features have emerged:

First, is the euphoria with which he has been received by the crowds wherever he has gone. It is a good sign for Chamisa, that despite the troubles that he has encountered with the Harare administration and its surrogates, the people are still on his side.

It was the first time that the court of public opinion was in evidence, and it responded with resounding affirmation, something that would have buoyed Chamisa no end and frustrated his rivals.

It was more delightful for him because these are rural areas that he is touring, not urban areas which are regarded as his zones of strength. It is, of course, too early but he has served notice to his rivals. If they thought the sustained assault during the pandemic year has worn him out, they realize they have a big fight on their hands.

It is more likely that Chamisa and his party gained more sympathizers at a time when the political assailants thought they were putting them out of the game. Besides, the reception has boosted his confidence after a period when some critics and naysayers were doubting him, some even suggesting without evidence that he had lost “considerable support”.

Politicians thrive on confidence and this will have helped them immensely.

The second feature is the violent response to Chamisa’s tour. It began in Masvingo where Chamisa’s advance party was physically attacked by an unruly mob, leaving vehicles and some members of the delegation injured.

His vehicle was also directly attacked when he traveled to Manicaland prompting fears and accusations of an assassination attempt. But why was there such a violent response to a simple tour? There is no election on the horizon to raise political temperatures.

This is an important question because the answer to that is not immediately apparent. Let us now look at the theories concerning the source of the violence.

Theory 1: The leopard will not change its spots

The first theory is that Mnangagwa is the principal author of the violence because that is consistent with his nature and record. If a hyena comes across a goat, its instinct is to kill and devour it.

Therefore, according to this view, the violence meted on Chamisa, and his delegation is just Mnangagwa acting true to his character and disposition. In other words, this is just Mnangagwa being Mnangagwa.

His political history is replete with acts of egregious violence. He oversaw state security and the ruthless spy agency during Gukurahundi. He was Mugabe’s campaign manager and strategist during the bloody presidential run-off election in 2008.

Violence is not a foreign language to the man. As a result, the moment Chamisa appeared to spread his wings the instinct was to respond with violence.

But still, it seems counter-intuitive for Mnangagwa to engage in violence purposefully and intentionally at this moment. This is a time when he is desperate to give a good impression of himself.

First, he is very excited by the prospect of travelling to the United Kingdom for the COP26 Summit in Glasgow. Although it’s a gathering to which all are invited to discuss the issue of climate change, Mnangagwa and people around him regard it as a special honour because it will be the first time that a Zimbabwean and ZANU PF leader will be permitted to visit the former colonial power in more than 20 years.

This is a big deal for Mnangagwa. That is why the propaganda machinery is touting it as a “success” in Mnangagwa’s desperate bid for re-engagement with Britain and the West. It would be strange, although not impossible, for him to batter his opponent so publicly when he has an opportunity to present a more civilized picture.

The second circumstance is that he has a special guest in the country whom he invited to bolster his anti-sanctions campaign.

Alena Douhan, from Belarus, another human rights hotspot, is in Zimbabwe as a UN Special Rapporteur to investigate the human rights implications of the targeted sanctions regime by the US and the EU.

Her itinerary, which is almost exclusively meetings with government and ZANU PF-aligned people, suggests that it’s little more than a hatchet job. They might have added a hint of subtlety by including even some friendly opposition parties and civil society groups and other stakeholders, but they could not be bothered.

Still, the fact is she is in the country and the image of ZANU PF supporters causing carnage in the opposition is not something that would serve Mnangagwa’s interests.

The purpose of the guest is to repackage Mnangagwa as a “victim” of Western sanctions. Why would he want to dilute it by victimizing the opposition leader in the full glare of the Special Rapporteur?

If anything, he would be better served by presenting a picture of mutual respect and toleration. Overall, although the theory that Mnangagwa is acting to type cannot be totally discounted, it seems unlikely because it is counter-intuitive and counter-productive to the man’s designs. There must be another explanation, but what could that be?

Theory 2: Political Theatrics

The second theory is one that is favoured by ZANU PF propagandists and supporters. It is that the attacks are no more than political theatrics by the opposition designed to soil Mnangagwa’s image at a time when he is about to enjoy some limelight on the international stage.

The reasons for the limelight are as described in the first theory above, namely, Mnangagwa’s impending trip to Britain for the COP26 which Mnangagwa’s people have packaged as a diplomatic success in the re-engagement process and the current visit by the UN Special Rapporteur, who is in Zimbabwe at the Mnangagwa regime’s special invitation.

They say because it is counterintuitive for Mnangagwa to hurt himself it must be the opposition that is staging the attacks to hurt him.

They also argue that whenever the regime is on the verge of something positive or whenever there is an international event, something terrible happens to the opposition and that this is because of the opposition’s machinations.

It is easy to see why this theory has appeal among Mnangagwa’s supporters and sympathizers. It is easy to believe that an opponent is self-harming to draw attention than to accept that the harm is coming from their own end.

ZANU PF has never taken responsibility for its violence. Four decades after Gukurahundi, ZANU PF is yet to take full responsibility and atone for the genocidal attacks on citizens in Matebeleland and the Midlands.

More than a decade after the egregious violence in the 2008 presidential run-off campaign, there has been no accountability.

However, the notion that Chamisa and the MDC Alliance are staging fake attacks to create negative attention and soil the Mnangagwa regime is fanciful for several reasons. Here, I will list three principal reasons as to why the theory of stage-managing attacks is implausible:

First, if the theory of fake attacks had any credence, the Mnangagwa regime would have spared no effort to prove it by arresting and prosecuting the alleged masquerades.

Why would the regime waste a great opportunity to prove that its rivals were engaging in political theatrics? It cannot be because there is no evidence. After all, there is ample video footage of the incidents from which offenders can be identified. If they were MDC Alliance supporters masquerading as ZANU PF members engaging in violence, there is no way the regime would let them go.

The regime has full control of the police service, and it would have been delighted to prove that the attacks were stage-managed. Police were present in some of the incidents, and they could easily have arrested the perpetrators.

They let them go and protected them because they are ZANU PF members who have always acted with impunity. Arresting them would only work to bust the myth of stage-managed attacks.

Second, at the first opportunity, ZANU PF defended and explained the conduct of the violent mob. When the ZANU PF political commissar Patrick Chinamasa reacted to the violence in Masvingo, he did not criticize the violence or the mobs. Instead, he alleged that Chamisa was at fault for trying to address people who did not want to be addressed by him.

If the violent mob was refusing to be addressed by Chamisa, how then do they turn out to be Chamisa’s people? How do people allegedly refusing to be addressed by Chamisa become the same people who are stage-managing false attacks?

Chinamasa was defending, not disowning the mob that had attacked Chamisa’s convoy. One cannot have his cake and eat it at the same time. The ruling party cannot defend and explain the actions of a violent mob and disown and accuse it of stage-managing the attacks at the same time.

Third, ZANU PF has always used the same line in its defence whenever its members and associates have attacked the opposition. If they do not blame the opposition, they point to a faceless and nameless “third force”. Victims of abductions and torture have suffered accusations of causing harm to themselves while perpetrators of the heinous crimes went free.

ZANU PF also has a long history of blaming victims. When Joshua Nkomo was facing similar attacks in the 1980s, ZANU PF ministers and the media were blaming Nkomo.

When Gukurahundi was raging in Matabeleland and the Midlands, they were blaming the ordinary people in the villages. ZANU PF blaming the opposition for its troubles is the typical default mode of the long-reigning ruling party. It never accepts responsibility.

For ZANU PF, there is always someone else to blame.

The theory of political theatrics and stage-managed attacks is convenient to ZANU PF but it is far-fetched and without foundation.

But it has also been argued that there is only a remote possibility of Mnangagwa being the directing hand of these attacks. If that is the case, who then is responsible for the attacks? This takes us to the third theory, which in my opinion, suggests a mounting problem for Mnangagwa.

While it might appear to exonerate Mnangagwa as the directing hand of the attacks, it suggests a certain precariousness of his position, which in many ways is not dissimilar to the problems that Mugabe faced at the tail-end of his long and controversial career.

Theory 3: The enemy lies within

This theory is that the attacks are instigated by a faction that is opposed to and working to undermine Mnangagwa because it is fed up with his leadership.

On this theory, while Mnangagwa faces a serious threat from Chamisa in the contest for national leadership, his most potent adversaries are closer to him. The only people who would want to do Mnangagwa harm and have the capacity to do so without facing immediate arrest are people within ZANU PF.

By contrast, even if the opposition were willing to harm Mnangagwa’s reputation, they don’t have the capacity to do so without facing immediate arrest and prosecution.

Mnangagwa is likely aware of this. He should know because the same strategy was used against Mugabe during his last years in office and he was the principal beneficiary, if not the author of it.

Several things happened during Mugabe’s last years in power that did not make sense because they only served to hurt him and his administration. Take, for example, the abduction and enforced disappearance of journalist and human rights activist, Itai Dzamara in 2015.

There was nothing to be gained by Mugabe for abducting Dzamara and causing his enforced disappearance. He was not posing a significant threat to the regime. Those who did it likely were either overzealous or they acted purposefully to raise pressure on Mugabe.

Additionally, many people were taken aback when Mugabe read the wrong speech at the opening of a Session of Parliament in September 2015. It was a big faux pas that embarrassed Mugabe and made international headlines.

His spokesperson George Charamba claimed it was a “mix-up of speeches”. Critical observers did not buy this explanation. Mugabe was 91 and his successors, among them Mnangagwa, was growing impatient.

Looking back, it is likely that the mix-up was more deliberate than accidental. It was designed to embarrass the aging leader and to show that he had lost it.

The irony is that the same strategies and tactics that Mnangagwa and his associates deployed against Mugabe are now being deployed against him. A few weeks ago, NewsHawks led with a story of how Mnangagwa’s legitimacy was being questioned within his party.

Just this week, in another case of a tortoise on a fence post, one Sybeth Musengezi, an obscure individual claiming to be a ZANU PF member made an application to the High Court challenging Mnangagwa’s ascendancy to the helm of the ruling party during the coup 4 years ago.

The issue is not whether the application has legal merit, but that 4 years after the coup someone dares to approach the courts to challenge Mnangagwa’s legitimacy.

As with any tortoise that you see on a fence post, the important question is how it got there because it couldn’t possibly have climbed on its own.

Someone is sponsoring the little-known Musengezi to challenge Mnangagwa’s legitimacy. Mnangagwa knows all about tortoises on fence posts.

Back in 2016, when he was Justice Minister and wanted to change the law for the appointment of the Chief Justice, one Lewis Zibani lodged an urgent application to stop the process that was already underway.

Zibani was a tortoise on a fence post. In November 2017, some obscure individuals lodged an application at the High Court asking for confirmation that the conduct of the military was lawful. Another application sought to invalidate the firing of Mnangagwa as Vice President a few weeks before. Those individuals were tortoises on fence posts.

An incident during the 2018 elections is also instructive. Chamisa and the MDC Alliance called a press conference at the Bronte Hotel.

However, riot police descended on the venue and stopped the press conference, harassing journalists in the process. It was an embarrassing incident that demonstrated intolerance and heavy-handedness. These actions were not in Mnangagwa’s interests, especially after the shooting of civilians on 1 August.

The deployment of the riot police had happened outside his command. A desperate Mnangagwa sent Simon Khaya Moyo to Bronte Hotel to reverse the decision and let the press conference go ahead. This was the closest he came to admitting that things were happening outside his immediate control.

In January 2019 he suffered embarrassment in the full glare of the World Economic Forum at Davos following yet another heavy-handed response to protests which left several people dead.

More recently, signs of internal dissent were evident when a small group of war veterans was arrested and detained after demonstrating at the offices of the Ministry of Finance and Economic Development.

They were released during the night. Perhaps the war veterans were simply audacious, but it is more likely that they had internal support to take such action. The midnight release was also a panic reaction to undo the damage of the arrests and detention which had happened without Mnangagwa’s knowledge. Long-term observers of Zimbabwean politics will remember that the last years of Mugabe were characterized by similar demonstrations and mistreatment of war veterans by the police.

They were open rebellions against Mugabe, threats from within. Mnangagwa will surely have taken notice of the small demonstration at the Ministry of Finance and its significance would not have escaped his attention.

Those behind the recent attacks on Chamisa and the MDC Alliance are gunning for Mnangagwa. It is his reputation that suffers.

Apart from reputation carnage, there is another purpose to these outrageous actions. It is to spur citizens into some type of mass action, perhaps a revolt against Mnangagwa. But he faces a dilemma: he cannot go after these attackers without exposing their sponsors who are in or near his inner circle.

Mnangagwa’s background is in intelligence. He might prefer to feign ignorance but may strike when the moment is opportune. Indeed, he may have struck already.

The other problem is that he cannot deny responsibility for what is happening without exposing his lack of control. For if it is not him doing it, it would mean there is another centre of power in ZANU PF directing these mobs and that would render him weak.

No leader, no matter how powerless he might be at any given time, wants to expose his weaknesses to the rest of the world. Consider the case of Mugabe.

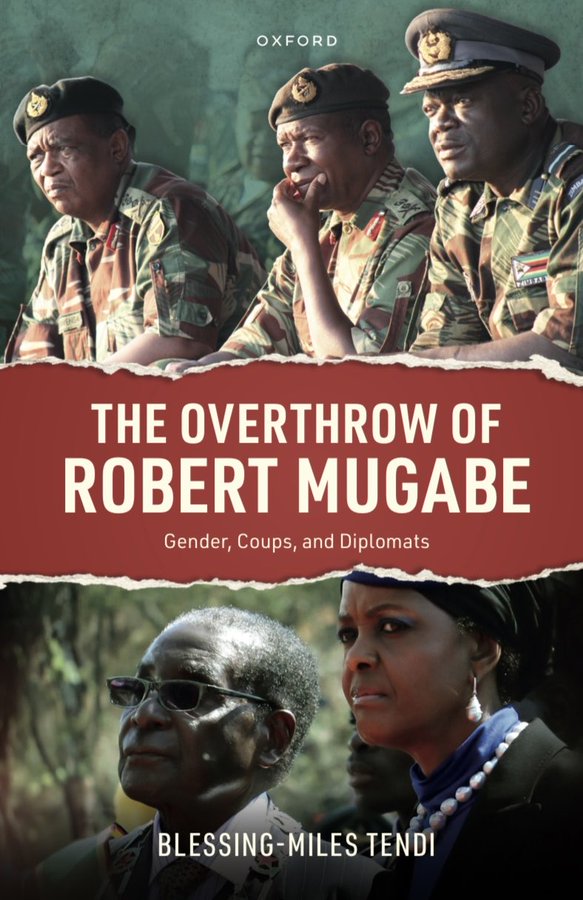

Right to the very end when he was toppled, Mugabe kept the pretence that he was in control. Interviews with individuals close to him at the time reveal that he refused to believe that his top lieutenants like Mnangagwa, Chiwenga, Shiri, etc, could turn against him.

He kept the charade going, even attending a college graduation ceremony during the coup week, even though it was clear to most observers that it was time up. Mnangagwa cannot be oblivious to these strategies. He was an architect in the slow process of eliminating Mugabe that ended with that dramatic week in November.

He will surely be aware that he has unhappy allies in his camp who are doing what they can to damage his reputation and oust him.

Why is this important?

This is ominous because he faces a twin challenge: the serious challenge posed by Chamisa. Despite the sustained political assault during the pandemic period, Chamisa appears to have emerged stronger and more refreshed.

His is a serious political challenge that Mnangagwa cannot afford to ignore. However, he hopes he can rely on the state and its machinery of coercion and cheating to thwart Chamisa. The second challenge is internal and probably the most potent.

These are near him; people who can use the strategies that Mnangagwa used against his predecessor. Unlike Chamisa and the MDC Alliance that are identifiable, the difficulty with the internal faction is that it is formless and harder to pin down.

This is important because it suggests that it is not just the traditional opposition forces that believe Mnangagwa is not fit for purpose. Rather, even those in his party seem to have realized that he has outlived his purpose and that it is time for him to go.

There is a group within ZANU PF that is not impressed with his bid for another five years in office. If he were watching this, Mugabe would probably wear a smirk at the sight of his successor facing the very same machinations that he so treacherously deployed against him.

WaMagaisa