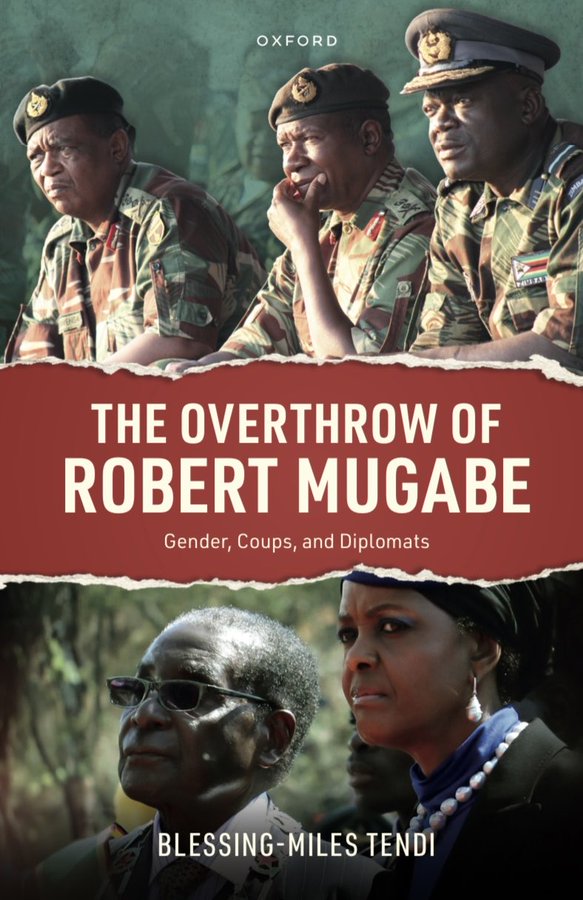

Image- Al Jazeera

The recent disclosure by Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe RBZ governor John Mushayavanhu that the government did not know much about Structured Currency, an World Bank idea, has left many thinking if this is not going to be another ESAP.

During a recent address to business executives, Mushayavanhu said he was not to blame for ZiG’s shortcomings as most of the input came from the World Bank official.

“We didn’t know much about a structured currency. We got a consultant from the World Bank. A lot of the things you’re seeing about the structured currency actually came from the World Bank.

So, if you’re going to blame me, you’re actually blaming the World Bank. Maybe they didn’t advise us properly. And if they did not advise us properly, it’s fine. Let’s refine it.”

In 1990, Zimbabwe launched a five-year Economic Structural Adjustment Policy (ESAP) substantially financed by the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and Western donor countries.

The expected dividends of ESAP did not materialise, and thus many critics blame it for the subsequent breakdown.

Others, however, believe that drought and failure to implement ESAP reforms effectively were responsible.

Why, then, was ESAP adopted? There were four problems. Firstly, restrictions on investment and on the right of foreign firms to remit profits curtailed investment.

This intensified the foreign exchange shortage, which made it difficult for firms to upgrade obsolete capital equipment and also limited job creation.

Secondly, subsidised prices and credit allowed businesses to survive without addressing inefficiencies. Thirdly, increases in civil service employment and spending on social services led to high taxes and a serious budget deficit, which was financed by public borrowing.

Fourthly, minimum wages and a system that required ministerial permission to retrench workers reduced employment.

Thus ESAP was introduced to encourage growth and employment, reduce state interference in the economy, improve access to foreign exchange, and reduce the deficit.

Yet ESAP is widely seen as an almost unmitigated failure. Growth was poor, employment contracted, many firms closed, and social services deteriorated. But the policies can’t be held solely responsible.

Circumstances were unfavourable when ESAP was introduced. There were disastrous droughts in 1992 and 1995, and a global recession in 1991/92 reduced raw material prices and export demand.

The biggest problem was the government’s inability to control the deficit.

This caused a sharp rise in interest rates just as local firms faced greater foreign competition. Liberalisation was implemented too quickly and not sequenced properly.

However, others say the results were not as bad as many people believe.

There was a robust recovery in 1996 and 1997, with significant increases in investment, exports and growth. But then, faced with increasing political opposition, ZANU-PF began to reward its allies, starting with a Z$ 4 billion payment to war veterans.

In 1998 the army entered the Congo and the breakdown began in earnest. The lessons to be learned from Zimbabwe’s experience are that 1) old-style interventionism will not solve the present impasse; 2) greater pragmatism should prevail; and 3) ESAP requirements for reducing the deficit were unrealistic, and a future regime will need massive donor support to introduce the necessary reforms.

Zwnews