Alex T. Magaisa

The situation in Nigeria has once again brought to the fore the challenges faced by citizens against trigger-happy and brutal regimes. They do not hesitate to apply excessive force, even if it results in the killing of unarmed citizens. One of the most touching stories is that of a young man, Oke Obi-Enadhuze who tweeted “Nigeria will not end me” on 21 October 2020. A few hours later, he was dead, killed by the security forces.

Here was a young man who was looking forward to the future and believing he would make it. His government ended those dreams through the barrel of the gun. Governments are enjoined by the constitution to protect, not to kill citizens.

But Oke was not the only victim of the Nigerian state brutality. Scores of his fellow citizens have been killed by their government during these protests, which were initially prompted by the brutality of the methods of a police unit, SARS, which was ostensibly designed to fight robbery. The unit was brutal and unpopular with citizens.

On 20 October, the Nigerian regime sent the military to Lekke Tollgate in Lagos where scores of civilians were massacred by the army. It was a terrible atrocity that has caught the attention of the world. Leading figures in Nigerian society both at home and abroad raised their voices on behalf of their fellow citizens and in condemnation of the regime.

However, what happened in Nigeria is not without precedent. Across Africa, many governments are at loggerheads with their citizens. The causes of friction range from a lack of commitment to democratic principles to poor and in many cases the absence of service delivery. When citizens protest, the regimes often respond by deploying the military and riot police.

This leads to a predictably bloody outcome, as military forces are not trained to carry out policing functions, let alone to respect fundamental rights and freedoms. The responsibility lies at the top of the command structure, the Commander-in-Chief, and the generals who oversee the soldiers.

Two years ago, when Zimbabweans protested during the general elections, the regime’s response was to deploy the military. Six people were killed. A commission set up to investigate the violence found that these people had been killed by members of the military and police. It was chaired by former South African President, Kgalema Motlanthe.

It recommended, among other things, that the perpetrators of the killings should be brought to account. To date, not a single person has been investigated or tried for the murders. The commission was a charade which the regime set up to hoodwink the international community into believing that something was being done.

The problem is that without accountability, it creates a culture of impunity. Since they know that they will not be held to account for the murderous conduct, members of the security forces can go on to do the same things again. Indeed, less than a month after the commission published its report, the Zimbabwean regime unleashed members of the military upon protesting civilians. On that occasion, 17 civilians were killed.

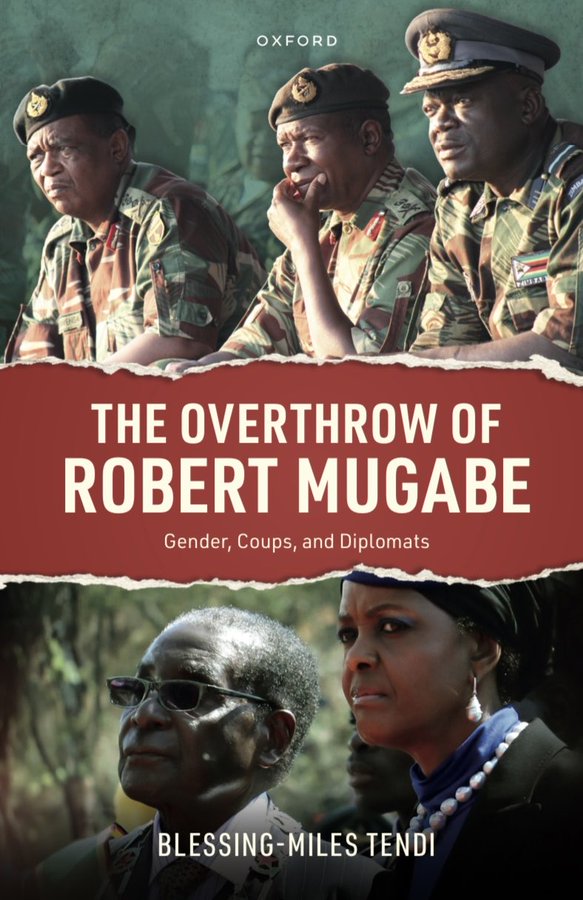

Ever since the coup that toppled Robert Mugabe in November 2017, there have been hundreds of abductions and torture of civilians. All of this is fuelled by a culture of impunity, which the regime encourages.

When Zimbabweans decided to go on another mass protest on July 31 this year, the regime again responded in typical fashion. Activists were abducted and tortured. In one case, a young student Tawanda Muchehiwa was abducted in broad daylight at a shopping centre in the city of Bulawayo.

He was held incommunicado for three days, during which he was severely tortured. Investigations by the media showed the full CCTV footage of his abduction, and the vehicle that was used to carry out the act was identified. It was hired from a car rental company, Impala Car Rental.

However, there has been no investigation by the regime. There is no appetite to investigate the flagrant violation of human rights. When a group of students demanded that the car rental company should give up information on the identity of persons who hired the vehicle, their leader, Takudzwa Ngadziore of the Zimbabwe National Students Union was himself abducted and tortured.

He was later arrested and kept in detention for a month. Another protestor Terrence Manjengwa who had come to court to support an opposition leader who was also in jail has been in custody for nearly two months.

This is the situation in Zimbabwe, where victims of crime find themselves jailed while perpetrators walk free.

Therefore, when Nigerians say #EndSarsNow and #NigeriaIsBleeding, Zimbabweans understand this all too well because they have also been crying out that #ZimbabweanLivesMatter. But Nigeria on the west coast of the continent and Zimbabwe to the south are only two of many other African countries in a similar predicament.

Cameroonians have long suffered under the authoritarian rulership of Paul Biya, who like some of his peers reportedly spends more time in foreign lands than in the country.

In Central Africa, the Congolese are crying out that #CongoIsBleeding, and in Namibia, they are running with #ShutItAllDownNamibia. In Uganda, the opposition is always on the receiving end of an intolerant regime led by a man who like Biya, has no appetite for life outside the presidency.

That there are hashtags is an affirmation of the newfound platforms of organising and solidarity among citizens. The hashtags are helping to create networks of cooperation among citizens facing brutal and repressive governments.

It was reassuring and encouraging for Zimbabweans when their #ZimbabweanLivesMatter gained traction around the world. Nigerian celebrities such as the internationally acclaimed musician, Burna Boy tweeted in support of Zimbabweans. This is why it has been easy and natural for Zimbabweans to identify with the cause of their Nigerian brothers and sisters.

Citizens are losing confidence in the formal networks of cooperation at the state level because they usually bend towards the interests of political leaders, not the long-suffering citizens. These formal organisations such as the African Union and regional blocs such as ECOWAS in West Africa and SADC in Southern Africa often operate as trade unions of political leaders. If they respond at all, it is often lukewarm and an after-thought. The statements are written out of duty rather than commitment. They are beaten to it by foreign organisations. Of the regional organisations, ECOWAS has in some cases shown some mettle, but SADC has generally been a disgrace. Even as the Zimbabwean regime was brutalising citizens, SADC pretended like nothing was happening.

Reading the response by Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari, it’s easy to imagine that the dictators have a manual they all refer to because it was exactly how Zimbabwe’s leader Emmerson Mnangagwa has previously responded to the atrocities committed by his regime. Muhammadu urged neighbours and the international community “to seek to know all the facts available before taking a position or rushing to judgment and making hasty pronouncements”. In other words, for Buhari, there is no crisis in Nigeria.

That is exactly how Mnangagwa responded when South Africa, the AU, and others began to raise concerns over the crisis in Zimbabwe in the wake of the #ZimbabweanLivesMatter movement. The Zimbabwean regime was quick to deny that there was any crisis in the country. It looks like the first rule in the dictators’ handbook is to deny whenever crises and human rights violations are mentioned. Dictators are quick to put down the shutters to avoid scrutiny from neighbours and the international community. They present the situation as if all is well and the citizens are the problem. They claim that the citizens are exaggerating the situation. No wonder South Africa has recoiled after it was bullied by the Zimbabwean regime when it tried to intervene. Buhari knows this works, hence the subtle warnings to its neighbours.

The dictators’ script also includes pointing fingers elsewhere and denying responsibility. So for Buhari, the demonstrations are caused by “subversive elements”, while for Mnangagwa any protests are supposedly sponsored by “regime change agents” or “dark forces”. Sometimes, where human rights violations cannot be denied, the Mnangagwa regime attributes it to “dark forces” or, to use their favourite term, “a Third Force”. There is no willingness to take responsibility.

There is also no acknowledgment on the part of these leaders that the citizens they lead have agency; that they have minds of their own to decide between right and wrong regarding how they are governed. They treat them like juveniles who can only act because they have been sponsored by “foreign” or “subversive” elements. It’s very disrespectful of the citizens and leads to denialism.

What is to be done in the face of abusive leaders who brutalise their citizens and refuse to take responsibility? They use the legal protection of their office to avoid domestic prosecution. After all, they often control the entire system, which makes domestic remedial measures ineffective while they are still in office and sometimes afterward. These protections and the knowledge that they can get away with murder gives these dictators more incentives to abuse citizens. This is why citizens end up looking to the international community for assistance.

This is not because the international community has a magic wand or that it consists of saintly nations and individuals. Indeed, as the longstanding crisis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo reminds us, some members of the international community do not have clean hands. Some of them are part of the problem, thanks to the voracious appetite for resources in capitalist economies, driven by the relentless pursuit of profit. In this scenario, human rights and other values become secondary considerations. That citizens in African countries end up pleading for external help is a sign of desperation. They should never be in that embarrassing position but the behaviour of their leaders and the lack of alternatives leads them down that path.

This is why some leading voices in Nigeria have called for sanctions against their leaders. The idea of sanctions is posited as punishment for their wrongdoing. It is also predicated on the belief that Nigerian political leaders desire access to Western countries and use their facilities, such as the financial system and healthcare system. President Buhari has in the past spent several months in foreign hospitals, itself an indictment on the Nigeran leadership which 60 years after independence has failed to build an efficient public healthcare system for citizens. Zimbabwe is 20 years younger but its leadership also relies on foreign healthcare systems, having utterly neglected the public healthcare system. The view of those calling for sanctions against their leaders is that they would feel the pain and perhaps reform their ways.

Yet, as Zimbabweans have discovered over the years, dictators have an uncanny gift of turning this weapon into a potent political instrument. Writing 15 years ago, I warned that the targeted sanctions would be converted into a political weapon by ZANU PF. It would play the victim, strengthening its argument that it was unfairly targeted by Western countries and that they were meant to aid an opposition that it characterised as a puppet of the West. Over the years, ZANU PF has made effective use of the sanctions’ narrative in its political campaigns, first locally and now more importantly, at the regional level. They have even managed to mobilise an “anti-sanctions day” roping in other countries in the SADC region.

Indeed, “sanctions” have the chief scapegoat for the country’s economic woes, even though the country’s troubles pre-date the imposition of targeted sanctions in the early 2000s. In any event, perpetrators of human rights violations have largely managed to circumvent these sanctions. Their funds are still held broad thanks to the prevalence of tax havens and an international financial system that has plenty of loopholes. Their children still study at Western colleges. They still get world-class healthcare abroad in countries like China, Singapore, India, and Dubai while their citizens are condemned to decrepit facilities.

So, while there might be some symbolism to the targeted sanctions, their effectiveness is doubtful, especially where the targeted have alternatives. They have not stopped repression in Zimbabwe, nearly 20 years later. Instead, they have been used as an effective propaganda tool against the opposition, which has to firefight each time the sanctions’ narrative is deployed. The sanctions’ propaganda is so ubiquitous that a casual visitor to Zimbabwe might believe that all of Zimbabwe’s challenges must be attributed to sanctions and have nothing to do with the regime’s ineptitude. This means the search for more effective ways to reign in dictators while they are in charge is still a project. The symbolism of targeted sanctions may have some appeal, but they must be measured against the costs to the opposition movements.

One possible mechanism to enhance accountability is to introduce the recall mechanism which enables citizens to directly terminate the president’s term of office before its official expiry date. There are already recall provisions in some constitutions, but they only apply to elected representatives in Parliament, not to presidents. The problem is that the politicians make these recall provisions so complicated and cumbersome that implementation is near impossible. In Uganda, the recall mechanism is provided for in the constitution, but it is suspended during the period of multiparty democracy. In Nigeria, the recall mechanism is almost impossible because of a high threshold for a valid petition before an elected representative can be recalled. In Kenya, the process is so long, complicated, and cumbersome that it is almost impossible to use it.

On the other hand, countries like Zimbabwe and South Africa do not even have a recall mechanism that enables citizens to terminate the term of office of an elected representative. It is probably a good time for African countries to seriously consider the use of recall mechanisms, which would enable citizens to have an option to recall their elected representatives, both at parliamentary and presidential levels, before the expiry of their terms of office. It would give citizens a perfectly lawful opportunity to register their unhappiness with the leadership during the term of office. After all, the authority to govern comes from them and they should be able to withdraw it when they are not satisfied with an incumbent’s performance.

However, there is an additional option. This is ensuring that brutal dictators and human rights violators are held to account in the international courts. If domestic courts are compromised, then international courts must be used more often. While the International Criminal Court (ICC) has been accused of targeting Africans, it is one important option for long-suffering citizens. In any event, the accusation against the ICC does not suggest that the African dictators are innocent. This is why the recent moves by the ICC prosecutor Fatou Besouda in Sudan are an important step. As stated by Deprose Muchena, Amnesty International’s Director for East and Southern Africa, “The ICC currently offers the most appropriate and timely recourse to justice while reform and strengthening of the weak and politically compromised justice system [in Sudan] is carried out”.

The ICC has a longstanding arrest warrant against Omar al Bashir, the deposed former dictator of Sudan who was protected by his African peers for many years despite the egregious human rights violations in the Darfur region. He is accused of war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity. If carried out to the end, the prosecution of al Bashir will serve as an important precedent to other African dictators who would otherwise think they were untouchable as he did during his long and genocidal reign. Holding al Bashir accountable will send an important message to current and would-be dictators that while they might get away with it in their compromised domestic systems, they will one day be held to account.

What is happening in Nigeria, Zimbabwe and other countries should not be tolerated. Some may dismiss hashtags, but they are helping to disseminate information across the continent in ways that were impossible before. In so doing, they are helping to grow consciousness among citizens, and as they see what is happening elsewhere, they realise their problems are the same and that they need to work in solidarity more than ever before. In that regard, the hashtag movements may be an important string in a continent-wide spider’s web, which one day may ensnare a dictator or two. They are important strings in building networks of cooperation amongst citizens who remain trapped in colonially demarcated boundaries but whose circumstances and experiences make them one.

It is important to note that in all these countries, the protests are often led by young people. This is hardly surprising. The continent is predominantly young in terms of population statistics. The rulers are often old men who are so far detached from the lived realities of young people. The generational gap is more evident now than it has ever been. The old generation of leaders is not in touch with the challenges that young, jobless Africans face. The conflict creates a potent powder keg and just as that old generation rose to fight colonial rule, so the young generation will rise to challenge an out of touch and brutal African leadership which lives in cloud cuckoo land.

WaMagaisa