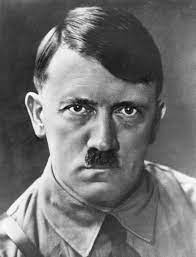

On the 20th of April, some133 years ago, Adolf Hitler was born in Braunau am Inn in Austria.

Zwnews has culled from online sources, a summary of Adolf Hitler’s life.

Hitler’s father, Alois (born 1837), was illegitimate. For a time he bore his mother’s name, Schicklgruber, but by 1876 he had established his family claim to the surname Hitler. Adolf never used any other surname.

Early life

After his father’s retirement from the state customs service, Adolf Hitler spent most of his childhood in Linz, the capital of Upper Austria. It remained his favourite city throughout his life, and he expressed his wish to be buried there. Alois Hitler died in 1903 but left an adequate pension and savings to support his wife and children.

Although Hitler feared and disliked his father, he was a devoted son to his mother, who died after much suffering in 1907. With a mixed record as a student, Hitler never advanced beyond a secondary education. After leaving school, he visited Vienna, then returned to Linz, where he dreamed of becoming an artist. Later, he used the small allowance he continued to draw to maintain himself in Vienna. He wished to study art, for which he had some faculties, but he twice failed to secure entry to the Academy of Fine Arts. For some years he lived a lonely and isolated life, earning a precarious livelihood by painting postcards and advertisements and drifting from one municipal hostel to another. Hitler already showed traits that characterized his later life: loneliness and secretiveness, a bohemian mode of everyday existence, and hatred of cosmopolitanism and of the multinational character of Vienna.

In 1913 Hitler moved to Munich. Screened for Austrian military service in February 1914, he was classified as unfit because of inadequate physical vigour; but when World War I broke out, he petitioned Bavarian King Louis III to be allowed to serve, and one day after submitting that request, he was notified that he would be permitted to join the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment. After some eight weeks of training, Hitler was deployed in October 1914 to Belgium, where he participated in the First Battle of Ypres. He served throughout the war, was wounded in October 1916, and was gassed two years later near Ypres. He was hospitalized when the conflict ended. During the war, he was continuously in the front line as a headquarters runner; his bravery in action was rewarded with the Iron Cross, Second Class, in December 1914, and the Iron Cross, First Class (a rare decoration for a corporal), in August 1918. He greeted the war with enthusiasm, as a great relief from the frustration and aimlessness of civilian life. He found discipline and comradeship satisfying and was confirmed in his belief in the heroic virtues of war.

Rise to power of Adolf Hitler

Discharged from the hospital amid the social chaos that followed Germany’s defeat, Hitler took up political work in Munich in May–June 1919. As an army political agent, he joined the small German Workers’ Party in Munich (September 1919). In 1920 he was put in charge of the party’s propaganda and left the army to devote himself to improving his position within the party, which in that year was renamed the National-sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (Nazi). Conditions were ripe for the development of such a party. Resentment at the loss of the war and the severity of the peace terms added to the economic woes and brought widespread discontent. This was especially sharp in Bavaria, due to its traditional separatism and the region’s popular dislike of the republican government in Berlin. In March 1920 a coup d’état by a few army officers attempted in vain to establish a right-wing government.

Munich was a gathering place for dissatisfied former servicemen and members of the Freikorps, which had been organized in 1918–19 from units of the German army that were unwilling to return to civilian life, and for political plotters against the republic. Many of these joined the Nazi Party. Foremost among them was Ernst Röhm, a staff member of the district army command, who had joined the German Workers’ Party before Hitler and who was of great help in furthering Hitler’s rise within the party. It was he who recruited the “strong arm” squads used by Hitler to protect party meetings, to attack socialists and communists, and to exploit violence for the impression of strength it gave. In 1921 these squads were formally organized under Röhm into a private party army, the SA (Sturmabteilung). Röhm was also able to secure protection from the Bavarian government, which depended on the local army command for the maintenance of order and which tacitly accepted some of his terrorist tactics.

Conditions were favourable for the growth of the small party, and Hitler was sufficiently astute to take full advantage of them. When he joined the party, he found it ineffective, committed to a program of nationalist and socialist ideas but uncertain of its aims and divided in its leadership. He accepted its program but regarded it as a means to an end. His propaganda and his personal ambition caused friction with the other leaders of the party. Hitler countered their attempts to curb him by threatening resignation, and because the future of the party depended on his power to organize publicity and to acquire funds, his opponents relented. In July 1921 he became their leader with almost unlimited powers. From the first he set out to create a mass movement, whose mystique and power would be sufficient to bind its members in loyalty to him. He engaged in unrelenting propaganda through the party newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter (“Popular Observer,” acquired in 1920), and through meetings whose audiences soon grew from a handful to thousands. With his charismatic personality and dynamic leadership, he attracted a devoted

The climax of this rapid growth of the Nazi Party in Bavaria came in an attempt to seize power in the Munich (Beer Hall) Putsch of November 1923, when Hitler and General Erich Ludendorff tried to take advantage of the prevailing confusion and opposition to the Weimar Republic to force the leaders of the Bavarian government and the local army commander to proclaim a national revolution. In the melee that resulted, the police and the army fired at the advancing marchers, killing a few of them. Hitler was injured, and four policemen were killed. Placed on trial for treason, he characteristically took advantage of the immense publicity afforded to him. He also drew a vital lesson from the Putsch—that the movement must achieve power by legal means. He was sentenced to prison for five years but served only nine months, and those in relative comfort at Landsberg castle. Hitler used the time to dictate the first volume of Mein Kampf, his political autobiography as well as a compendium of his multitudinous ideas.

Adolf Hitler, byname Der Führer (German: “The Leader”), (born April 20, 1889, Braunau am Inn, Austria—died April 30, 1945, Berlin, Germany), leader of the Nazi Party (from 1920/21) and chancellor (Kanzler) and Führer of Germany (1933–45). He was chancellor from January 30, 1933, and, after President Paul von Hindenburg’s death, assumed the twin titles of Führer and chancellor (August 2, 1934).

Hitler’s ideas included inequality among races, nations, and individuals as part of an unchangeable natural order that exalted the “Aryan race” as the creative element of mankind. According to Hitler, the natural unit of mankind was the Volk (“the people”), of which the German people was the greatest. Moreover, he believed that the state existed to serve the Volk—a mission that to him the Weimar German Republic betrayed. All morality and truth were judged by this criterion: whether it was in accordance with the interest and preservation of the Volk. Parliamentary democratic government stood doubly condemned. It assumed the equality of individuals that for Hitler did not exist and supposed that what was in the interests of the Volk could be decided by parliamentary procedures. Instead, Hitler argued that the unity of the Volk would find its incarnation in the Führer, endowed with perfect authority. Below the Führer the party was drawn from the Volk and was in turn its safeguard. britannica.

Zwnews