By Alex Magaisa

A hatchet job

Few issues divide public opinion like sanctions. Debate is not so much over their existence, but their nature and impact.

As with most political issues, the sanctions issue is framed in binary terms. We have already observed in previous analyses that binary framing tends to conceal more than it reveals.

Complex matters are not amenable to “either/or” framing because a lot that lies in between or beyond tends to get lost.

The issue of sanctions has drawn the limelight following the visit of Alena Douhan at the invitation of the Zimbabwean government.

Douhan who hails from Belarus, a country that is equally notorious for human rights violations, came to Zimbabwe in her capacity as a UN Special Rapporteur on the matter of sanctions. She presented her preliminary report on 28 October 2021, urging the lifting of sanctions and calling for dialogue.

If she was supposed to be an impartial and objective investigator, her itinerary which the government shared betrayed her mission as a hatchet job. It was a pro-government line-up with no sign of other stakeholders.

In the process, she did meet a few other stakeholders but if this was meant to cover the glaring bias of the original itinerary, the end was as embarrassing as the beginning after a press release of her report was released while she was in a meeting with representatives of the MDC Alliance, the major opposition party which is persecuted and ostracised by the regime.

This revealed that the meeting was no more than a box-ticking exercise and the report was written before the investigation was completed.

Douhan’s report has also been red flagged for plagiarism. She has been accused of lifting chunks of material from her previous reports in other countries and used them in her report on Zimbabwe.

This unethical conduct strikes a blow at the credibility of her report and must be a source of embarrassment to the United Nations under whose name the work is performed.

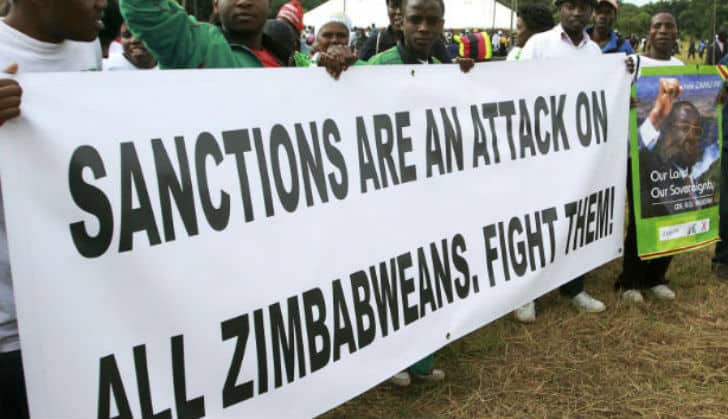

That it was a hatchet job was never in doubt. The timing of her visit, when the regime hosts its anti-sanctions day on 25 October each year was not a coincidence.

Her visit with the UN flag being touted for authority was designed to bolster and amplify the ZANU PF regime’s anti-sanctions campaign. To the extent that the sanctions issue has dominated the headlines and drawn the attention of both the sanctioning countries and the sanctioned targets, one has to admit that the regime’s strategy to make sanctions the issue has worked.

It has successfully mobilized most regional leaders to support its anti-sanctions cause and, in the process, carved out a useful image of victimhood.

A cautionary note from 2005

Back in 2005, writing in the Zimbabwe Independent, I made a cautionary note regarding the targeted sanctions that had recently been imposed by the US, the EU, Australia, and Canada.

Although the show of solidarity with the suffering people of Zimbabwe was understandable, I was concerned that sanctions would eventually become both a shield and weapon for the Mugabe regime.

I was sceptical about the effectiveness of sanctions and there was literature to back up that scepticism. But worse, I thought sanctions would become a shield because the regime would use them as a scapegoat for the country’s economic ills, deflecting attention from its failings.

I worried that they would become a weapon because the regime would use them to beef up its attack on the opposition as a Western puppet and regime change agent.

Mugabe had already built a powerful narrative that caricatured the MDC as a Western-sponsored party. These narratives were easy to sell to the largely rural population, especially the hundreds of thousands that had recently got land from the farm invasions.

Mugabe told them the sanctions were imposed to punish him and his government for taking back the land.

Events over the past two decades have shown that this cautionary note was not far from the target. Both Mugabe and his successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa have, as predicted, used sanctions as a shield and a weapon, just as predicted.

They have used it as a shield against regional criticism. Instead, they have harvested solidarity in the face of glaring human rights violations and gross electoral irregularities.

Even some people in the business community who notoriously shy away from commenting on corruption, human rights violations and electoral cheating arguing that they do not dabble in politics suddenly find their voices when it comes to the issue of sanctions. It’s an easy subject because it does not ruffle government feathers.

However, ordinary people have more wisdom than regional and business elites. They know that the cause of their problem lies within, not outside. A recent survey by Afrobarometer shows that 65% of Zimbabweans believe that the country’s economic meltdown is down to mismanagement and corruption by the government.

By contrast, only 29% blame sanctions with the remaining 7% being non-committal or refusing to answer the question[1]. Clearly, while the anti-sanctions propaganda has been incessant, most Zimbabweans know that the source of their problems is within.

Still, it is important to take a closer look at this issue of sanctions because the regime is not going to stop pushing it down people’s throats as the country moves towards the next election.

Exercising power

To be sure, sanctions are controversial instruments wherever and whenever they are deployed, and many scholars do not believe that they are effective[2]. Sanctions are an instrument of foreign policy by the imposing state.

There are several logics or rationale of sanctions, which I shall examine in this article. However, by and large, when sanctioning is used, the imposing state or organization is exerting its power and influence over the target state or group.

The imposing state or organization wants the target state or group to comply with its standards or expectations or simply to pay a penalty for non-compliance.

It is not only states that impose sanctions against others. They can be imposed by organizations and networks the biggest of which is the United Nations. At the informal end are organizations like the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) which is sets rules and standards in the global fight against money laundering.

It expects both its members and non-members to comply with its set of recommendations failing which they are designated as non-compliant. Once blacklisted like this, businesses in member states are prohibited from doing business with businesses in the blacklisted state.

Sanctions also come in various forms. They can be general economic sanctions that prevent trade with a state or they can be targeted in that they focus on specific individuals or entities within a state. In either case, they represent an exertion of power by the imposing state.

The regime of sanctions in Zimbabwe falls into the latter type. Mugabe, his allies, and associated corporate entities were specifically targeted. The restrictive measures included travel bans, financial restrictions, and asset freezes.

As we have already observed, the question of whether sanctions have caused economic damage in Zimbabwe usually attracts a binary response. This is in keeping with the political polarisation in the country. The first, favoured by ZANU PF and its allies is that sanctions have grossly harmed Zimbabwe’s economy. The second, favoured by the MDC Alliance and its allies is that Zimbabwe’s economic problems are a result of mismanagement and corruption, not sanctions. They see sanctions as a red herring. We have already seen from the results of the latest Afrobarometer Report the majority (65%) share the view that is held by the MDC Alliance while only 29% share ZANU PF’s view.

Nevertheless, as with most binary approaches, it conceals more than it reveals. Perhaps a multi-factorial approach is better in that all factors have a role in weighing down the economy and the real difference is a matter of degree. Let us move on now and examine the logic of sanctions and assess the impact and success or failure of sanctions 20 years after they were imposed.

The Logics of Sanctions

In his paper “How EU sanctions work: A new narrative”, Francesco Giumelli provides a useful account of the logic of sanctions[3]. The three logics of sanctions that he identifies are Coercion, Constraining, and Signalling. I will explain each in turn, demonstrating why a full appreciation of this logic matters to the debate concerning sanctions in Zimbabwe. It might shed more light on why they were imposed, why they took the form of targeted sanctions, and what the impact has been over the years. An examination that looks at the different logics reveals that the question of whether they have succeeded or failed is more complex than first appearances suggest.

Coercion

The first and most cited logic of sanctions is that they are meant to coerce the target into changing its behaviour or policies under the threat of damage. The purpose of coercion is to lead to behavioural or policy changes. As Guimelli points out, this is based on the so-called “Pain-Gain” equation whereby a party is subjected to pain so that it is forced to reform. A domestic equivalent is the withdrawal of an allowance by a parent to force the child to comply. In this view, sanctions impose costs that a party must avoid by changing its behaviour. A party must weigh the costs and benefits and conclude that it is better to comply than to defy and incur costs.

One might cite sanctions that were imposed on Smith’s Rhodesia following his unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) in 1965. They were UN-backed comprehensive sanctions that were designed to prevent trade with Rhodesia. The Black nationalist parties such as ZANU and ZAPU called for those sanctions as an advocacy tool to get the Smith regime to back down and pave the way for majority rule and independence. They were designed to cause damage to the economy and put pressure on the Smith regime. The regime managed to stay afloat for some time, thanks to sanctions-busting strategies and assistance from its ally Apartheid South Africa. However, as the Apartheid regime threatened to withdraw its backing, the Smith regime was left vulnerable and had little choice but to capitulate in 1979. But sanctions were only one of the tools in use. There were other tools, such as the armed struggle and international diplomacy which all contributed to the successful outcome.

We have observed that in terms of this logic of sanctions, coercion is all about forcing behavioural change in the target or producing a specific policy change. In this regard, the US Congress’ Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act (ZDERA) is an example of a tool that was designed to promote behavioural and policy changes by the Zimbabwean government. The same applies to the Executive Orders and the restrictive measures that were imposed by the EU. Its success or failure may therefore be judged on whether it has produced the required behavioural or policy change. Much depends on the questions that are asked. If we assume that the sanctions were designed to change the ZANU PF government’s attitude to human rights and democracy, then so far, they have failed to produce the desired behavioural changes. The comprehensive change to the constitution in 2013 and related laws however might count as positive steps in the fulfillment of policy changes.

Also, if we assume that they were designed to coerce the government into holding free, fair, and credible elections, the sanctions have so far failed to produce behavioural change. However, if we assume that land reform and property rights were at the core of concerns, then the signing of the Global Compensation Agreement under which the government promised to pay compensation to white farmers who lost their farms during the FTLRP, the sanctions might be seen as a success. The Zimbabwean government has moved from the rhetoric of expropriation without compensation to making a legal commitment to pay compensation. The Mnangagwa regime took that step hoping to pacify the sanctioning states.

However, as Guimelli points out, it would be erroneous to see coercion as the only logic of sanctions. He is critical of most of the analyses that limit the assessment of sanctions to the logic of coercion.

Constraining

The second logic of sanctions is they have a constraining effect on the target. This is where sanctions are imposed to weaken the target by limiting its capabilities. Guimelli gives the example of an international terrorist group, where there is very little prospect of causing behavioural change through the coercive effect of sanctions. The logic of sanctions in such a situation is to weaken the group’s ability to organize and carry out terrorist attacks.

This could take several measures such as financial restrictions, asset freezes, travel bans, etc on the targets. In this case, you cannot measure the success of sanctions by assessing if there is any behavioural change in the group, but probably by whether its capacity to organize and launch terrorist attacks has been weakened. This logic of sanctions does not seem to have much application to the case of sanctions in Zimbabwe except in two instances: the arms embargo against the Zimbabwe Defence Industries (ZDI) and the financial restrictions on corrupt individuals and networks. The restrictions are designed to weaken their capacity to move illicit funds through the international financial system[4]. However, since these logics are not mutually exclusive, such restrictions might also have a coercive effect as they are designed to coerce corrupt targets to change their behaviour.

Signaling

The third logic of sanctions according to Guimelli is their signaling effect. This means sanctions against a target are designed for a broader audience beyond the target. The aim is not so much to hurt the target but to send a signal to a broader audience. For example, if a target is violating an international norm, a state might impose sanctions on it as a way of sending a message regarding the importance of that norm. Sometimes a state imposes sanctions as a way of expressing solidarity with another sanctioning state or persecuted groups. One might also add that one signal might be a deterrent effect. This is where sanctions are designed to deter others in the audience from taking a similar path.

The right to private property is regarded as a basic norm in Western economic society. The rampant disregard and destruction of private property rights during the FTLRP was a serious cause for concern for Western governments. It could not be allowed to pass without rebuke. The message was relevant, not just to the target, in this case, Zimbabwe, but to a broader audience in the region. In this regard, South Africa and Namibia, states with similar historical imbalances regarding land ownership rights, were part of the audience. Sanctions in Zimbabwe represented an important symbol of disapproval to the type of land reform that had taken place there, which was essentially expropriation without compensation. If we look at the sanctions from this angle, one might argue that with South Africa and Namibia both stalling on land reform, the signaling effect of the sanctions has been quite successful.

Generating dissent

Guimelli’s taxonomy of three logics of sanctions is useful but it may be argued that there are more than three. One is that sanctions are designed to increase the wedge between the target government and the citizens. In the case where the pain of sanctions is felt by the citizens, if the government does not comply, they might be spurred into action against it to prevent further suffering. The logic is that faced with intense hardships, citizens will rise against their government. This might be called a sanctions-induced uprising. This is a subset of the coercion theory because a government that wants to avoid a sanctions-induced uprising will take pre-emptive action of compliance so that citizens are spared the full effects of sanctions.

In the case of Zimbabwe, this logic would be more applicable if there were comprehensive economic sanctions against Zimbabwe as a whole. They would not be targeted at specific individuals and entities. Zimbabwe is not under trade restrictions. It can and does trade with all the countries that have imposed targeted sanctions. That’s why Zimbabwean produce can be found on supermarket shelves in all these countries, just as Zimbabwe can buy Ford Rangers and Range Rovers manufactured by companies in the sanctioning countries. As for loans from the World Bank and the Paris Club lenders, Zimbabwe simply needs to clear its arrears and get back into its good books. Sanctions are not the reason why the country cannot access credit. Zimbabwe was long blacklisted by creditors before the sanctions were imposed.

The Boomerang Effect

The problem with sanctions in whatever form is that they can have a boomerang effect.

In a situation where they impose an economic burden on citizens and cause hardship, the logic is that citizens must see that their government is a problem. But it might have a counterproductive effect where citizens see the sanctions, and not their government as the problem. A government that is adept at turning a bad situation into a weapon can make effective use of sanctions for its own survival. It will use the existence of sanctions as the scapegoat for the economic ills of the country. As Guillem points out, “Target governments tend to blame sanctions for their country’s economic problems and strengthen the will of the people to resist the pressure as a way of stirring up national pride and protecting national independence”.

You will recall that this was the warning that I wrote in 2005 that the ZANU PF regime would use sanctions to its advantage. This is what I wrote back then in an article entitled “Smart Sanctions: Who do they really hurt?”,

“Sometimes the government plays victim – arguing to its citizens that it is the victim of powerful Western states that hate the country. The government presents itself as the heroic saviour of the people against imperialists with the duty to guard jealously the country’s sovereignty.

Those who are exposed to other sources of information and therefore able to exercise informed judgment might dismiss the effect of such rhetoric as nonsense. But they also underestimate the effect of such messages on the general population, which is repeatedly bombarded with the same messages that they end up believing it is true.

The problem here is that sanctions give credence to the rhetoric that the problem is external – that the fight is about sovereignty.”

My objection was not that I did not believe perpetrators of violence and electoral cheating did not deserve international censure.

It was because I feared a set of sanctions that did nothing to cause behavioural or policy changes would only become a weapon by the regime. To the extent that sanctions have not caused any significant behavioural or policy changes, the coercive logic of sanctions has not been fulfilled. Admittedly, they may have had a signaling effect deterring countries like South Africa and Namibia from taking the Zimbabwean path. However, given the way African countries have rallied around the Zimbabwean regime on sanctions despite its authoritarian rule, human rights violations, compromised elections, their existence has had a boomerang effect. Far from weakening the regime, they have strengthened its bonds with its peers, making the task a lot harder for the opposition.

Missing the targets

When sanctions were introduced, they were referred to as “targeted sanctions”. The idea was that these were different types of sanctions that would not affect the generality of citizens. They are based on the theory that because they are targeted, they only affect the targeted individuals and entities. They include, as we have observed, travel bans, financial restrictions, and asset freezes.

The problem is that this type of sanctions is easy to circumvent so that the personal inconvenience they cause is limited. While Mugabe loved his regular trips to Britain and might have wanted his children to get educated at its exclusive public schools, when he was banned, he simply switched to the Far East. Other individuals who were targeted did the same with places like Dubai offering alternative destinations of luxury and convenience. As the Panama Papers and the Pandora Papers showed, the wealthiest Zimbabweans who were under targeted sanctions were still able to move their millions through complex corporate structures in offshore finance centres like Mauritius and the Cayman Islands.

The targeted sanctions may have caused the targets some minor personal inconveniences, but ultimately, they always found a way to carry out their nefarious activities. If anything, the levels of corruption have increased despite the targeted sanctions. If therefore sanctions were designed to cause a behavioural change, they have failed to achieve that purpose.

But the problem is while the targeted sanctions are not effective in changing the targets’ behaviour, the regime still finds sanctions as a useful shield to deflect attention and a weapon to attack the opposition. To the regime, sanctions are the gift that keeps on giving.

Over-compliance

While the theoretical distinction between general and targeted sanctions sounds persuasive, in practice it is limited. This is because while targeted sanctions are designed to be narrow in their effect, the outcome is more general because of the problem of over-compliance, one of the more valid points identified by Douhan.

Over-compliance occurs when businesses dealing with individuals and entities from countries where targeted sanctions were imposed take an overly cautious approach to everyone from that country which ends up affecting innocent persons. Ideally, targeted sanctions are supposed to affect only the targeted individuals and entities.

But in practice, because of the duty to avoid breaching targeted sanctions, businesses over-comply and end up hitting innocent parties. When this happens, the personal inconvenience of targeted sanctions goes beyond the targets and becomes a problem for the general population. Innocent citizens become “collateral damage” because of over-compliance with targeted sanctions. It is for this reason that some Zimbabweans and businesses have quite legitimately protested that the targeted sanctions have affected them even though they are innocent parties.

Conflating issues

However, targeted sanctions are not the only reasons why ordinary individuals and businesses suffer inconvenience on the international markets.

For example, there are other impediments to accessing credit or performing international transactions which have nothing to do with sanctions. Take the Financial Action Task Force’s restrictions for example. The FATF blacklists countries that are not compliant with its rules and when it does so, individuals and businesses from blacklisted countries struggle to do business with entities from other countries.

Since Zimbabwe has not been fully compliant with the recommendations of the FATF, this might lead to financial institutions from other countries taking an overly cautious approach when dealing with Zimbabwean entities and individuals. In addition, Zimbabwe’s perennial currency challenges and extremely limited foreign currency reserves impact the ability of entities to perform international transactions. The fact that the country is in arrears going back more than 20 years limits its ability to access credit.

However, for the regime and others who look at these issues without a critical eye, all these impediments are lumped together and blamed on sanctions.

Conclusion

I have never been a fan of sanctions, general or targeted because I do not believe they work effectively as instruments of behavioural or policy change. The targets often dig in or circumvent them.

Ove-compliance might lead to collateral damage beyond the targeted individuals and entities. But more significantly, authoritarian regimes are adept at turning the adversity of sanctions into an advantage. The Zimbabwean regime has worked hard to turn the lemons of sanctions into the lemonade of political capital. It has won on the regional front, where it has gained solidarity from peers who should be calling it to order. Thankfully, as the Afrobarometer Report shows, the majority of Zimbabweans do not blame sanctions for their economic ills. They place the blame on the government, where it belongs. The Afrobarometer survey is the scientific poll that we have had in recent years. The government has referenced it when its findings favour it, therefore it cannot now dismiss it because of this finding.

Perhaps a more important point to appreciate is that sanctions are not the only foreign policy tool but one of several. They are certainly not worse than war, but there are other tools such as diplomacy and negotiation. It was important for Zimbabweans who were fighting authoritarian rule to get the attention of the international community. If the international community had not acted, it would have been accused of willful negligence just like what had happened during Gukurahundi just 20 years earlier when it stood by and ignored the plight of the people of Matebeleland and the Midlands as they were butchered by the Mugabe regime. The EU has adapted to the times, using dialogue, diplomacy, and technical assistance as other tools to achieve the same ends of promoting democracy and human rights. This flexibility is not unimportant, especially when dealing with a complex problem like Zimbabwe.

Every policy instrument however requires regular review. Such reviews would tell whether the targeted sanctions regime is working effectively; whether it is producing positive results or whether it has become counter-productive. I was always skeptical of the efficacy of the targeted sanctions regime, but my greater worry was that they would be weaponized by the regime and I think this has come to pass.

I conclude with some food for thought: there is a distinction between actual sanctions and the threat of sanctions, and in my opinion, the latter might be more effective than the former.

The power of a threat lies in its unknown quality. It is better when someone does not know what might happen if the threat is carried out than if the threat is carried out it turns out it is not that bad after all. Once the target has discovered that the threatened experience is harmless, it will carry on misbehaving. At that point, the sanctioning authority will have to find a new way to handle the problem. I suspect every parent or guardian has a fair appreciation of this challenge.

WaMagaisa